In this series of blogs we're exploring the various OSR RPG systems out there and how they compare to one another and the D&D rules throughout the ages. Last week we took a look at Dungeon Crawl Classics.

This week we're looking at the The Mecha Hack by Absolute Tabletop which is a roleplaying game of titanic warmachines powered by The Black Hack.

As a system it demonstrates how you can take the core chassis (excuse the pun) of an OSR game ostensibly made for fantasy and port it to a wildly different genre with excellent results. In much the same way as Mothership did for Sci-Fi Horror.

The Mecha Hack is a game where you play as a group of intrepid pilots who control titanic warmachines and send them into heated situations within a war-torn science fiction world. It follows a lineage of games and media ranging from the Battletech/Mechwarrior tabletop and video game series, to tabletop RPGs such as Lancer and films and anime such as Evangelion or Pacific Rim. These all explore the fiction of mankind developing giant robot warmachines and then blowing up each other or giant Godzilla like monsters with them.

As with the Black Hack the Mecha Hack uses a core d20 roll under resolution system. To succeed at something in the game you must roll under one of your core stats that relates to that task within the game. The Mecha Hack also uses the advantage/disadvantage system that The Black Hack uses as well as 5E D&D. This allows you to roll two d20 and highest or lowest result respectively based on the situation. For example sneaking up on a foe and attacking may grant advantage whilst fighting a Godzilla like kaiju foe whilst your mecha is submerged underwater may grant disadvantage.

In the Mecha Hack the 4 stats are Power, Mobility, System and Presence. These represent the characteristics of the Mech you control in the game. Power is for tests of strength such as flipping over a car as well as firing weapons such as beam rifles. Mobility is for dodging out of the way of laser beams or sneaking, as best a Mech can, through a ruined city. System tests are for scanning hostile foes or scrambling enemy communications. Presence is a measure of personal resilience and influence and includes the likes of instilling awe or reverence in allies, intimidating enemies or overcoming fear and uncertainty.

These are broadly similar to the stats found in The Black Hack but condensed down to 4 and built to be more relevant to a Mech as appropriate for this game.

These stats are rolled randomly from the total of 3d6, as in The Black Hack and the vast majority of ‘OSR’ titles harkening back to Original D&D. The Black Hack does allow two stats to be swapped and includes the similar Black Hack rule that if you roll a 15 or higher on one attribute the next must be rolled with 2d6+3 to create a character that’s a bit more balanced.

Once you’ve rolled your stats you choose a Pilot for your Mech from a choice of commander, engineer, maverick and quipster. This provides a bonus to a handful of your Mech’s attributes as well as some unique abilities. The Commander for example adds 2 to your Power and 1 to your Presence and allows you to ‘command’ other Mecha giving them additional actions in combat similar to the Warlord Class in 4E D&D.

If this were a more traditional fantasy game then your Pilot choice would be similar to choosing a ‘Race’ in a game such as Basic Fantasy. The choice provides some bonuses and roleplay opportunities to your character but doesn’t define them as much as a class would. The challenge in designing a Mech game that also wants to be rules lite is having effectively two separate characters, your pilot and your mech. Subverting the ‘race’ mechanic from other games is a quick, simple and familiar means to have a pilot/mech split that’s a lot easier than tracking two separate characters.

It’s worth noting there are some rules at the back of The Mecha Hack that briefly cover playing with just your Pilot, but the core of the game is intended to be players controlling their Mech’s.

Which brings us to the meat of the game, choosing your Mech Chassis. There’s four to choose from, a brawler, scout, striker and titan. These determine the core of your Mech’s abilities as well as their health, damage and reactor die and effectively act as your character ‘class’.

They follow this logic loosely as well mirroring the 4 classes from The Black hack that themselves mirror those from original D&D. The Brawler is your ‘Fighter’ excelling at close distance fighting and outlasting foes in combat. They get a high d8 hit die, reactor die and damage die, can use all weapons and armour and have abilities that give them extra chances to deal critical hits.

The Scout is your ‘Thief’ equivalent. They are light, quick mecha good at concealing themselves with the likes of cloak generators. They come with a standard d6 across their hit, damage and reactor die and can use all light weapons, armour and shields. They get access to slick abilities such as their cloaking field which makes them hidden from foes and a means to Ambush enemies for advantage to hit and additional damage.

The ‘Striker’ is loosely analogous to a caster equivalent. They are a well balanced mecha that excels at utility and have the ability to restore reactor energy to their allies. This allows them to improve the reactor die of an ally by one step up to its maximum. They get a d8 across their hit, damage and reactor die and access to light armour, all weapons and shields. They can also re-roll any result of a 20, which in The Black Hack is the equivalent of a critical failure.

The Titan is a huge, heavily armoured mecha that excels at brute force, absorbing damage and protecting allies. It’s analogous to a Fighter or even Barbarian but the analogies break down a bit at this point as it’s really its own entity. It gets a huge d10 hit die and d6 damage and reactor die. It can use all weapons and armour and has abilities that allow it to absorb damage that other allied mecha suffer and create energy shields to protect itself and allies from damage.

Each mecha gets a set of starting equipment relevant to their chassis, for example the Brawler gets a laser axe whilst the Titan gets a heavy chaingun, and can choose a module to customise themselves with. These have effects that range from shooting chest laser beams to shrouding yourself in nanites to regain armour points.

You can optionally also have 120 credits to buy weapons and gear with if you don’t want to use the starting loadout. This number mirrors the slightly above average amount that you’d generate by rolling 3d6 x 10 which is what you rolled for your starting gold in Basic D&D. Then you’re basically ready to start the game!

Many of these elements such as Hit Points and Damage will be familiar to you if you’ve played D&D or any OSR variant, however the Reactor Die is unique. It represents the reactor that powers your mecha and works in a similar way to the usage die in The Black Hack. When you activate certain abilities, take the same action twice in one turn or take a critical hit you have to roll your Reactor die. If you roll a 1 or 2 the die is downgraded to the next lowest die in the chain. So if you’re a Brawler with a d8 reactor die you’ll reduce down to d6, then d4. When you roll a 1 or a 2 on a d4 reactor die your mecha becomes overheated meaning it cannot take actions and has disadvantage on all checks. You must spend a turn to expel heat and cool off before. The only way to restore is via rest.

This is a clean and simple way to represent overheating which is a common risk/reward element in mech games such as the classic Battletech/Mechwarrior series. It means pushing your mecha to do more things results in more chances that they will overheat and their reactor will deteriorate accordingly. This balances out the various cool abilities each mecha has access to as most force reactor roll checks which means the likes of The Scout’s cloaking field can’t be spammed.

The core of play still plays in a familiar way to most traditional role playing games. One player takes the mantle of the Games Master (GM) and sets up the game world and scenario for the players to play through, acting out the part of all the characters in the world and describing what happens as a result of the players actions. The players play as an individual character or in this case mecha and pilot..

The game does focus itself around a mission structure, providing lots of random tables for the GM to create scenarios with. Missions in the game are significantly more bombastic than your average fantasy game, with players potentially battling Kaiju over a ruined city or delving into a Lunar colony to do battle with a group of powerful experimental mecha. These random tables link to some of the core principles of ‘OSR’ games in particular emergent play.

Combat and action scenes play out in a fairly familiar way at least on paper. Turns are taken in initiative order. Mecha can take two actions of their turn such as moving, attacking, testing an attribute to do a task, or using an ability. If you do the same action twice in a turn you must roll the reactor die. Attacking primarily uses a ‘Power’ roll to determine if you hit.

As with The Black Hack your core stats are effectively also your ‘saving throws’ and the way you avoid attacks in combat. If for example your mecha is attacked by a Kaiju you would have to roll a mobility test to avoid taking the damage.

This is a big departure from original & basic D&D as well as retroclones such as Old School Essentials which use both static armour values and static saving throw values per class. In these games to attack someone you roll against their armour class and attempt to beat it. If something happens to you such as being shot by a fireball you have to roll a saving throw to avoid it split up into various categories.

Mork Borg does use a similar system to the Mecha Hack in that players roll a d20 stat check to avoid hits in combat as well as other effects although within Mork Borg this is roll high against a DC.

Ranges are abstracted into 4 categories of close, near, far and distance similar to Forbidden Lands as well as of course The Black Hack. This differs from the likes of Basic D&D or retro clones such as Dungeon Crawl Classics which use specific real world distances for their weapon and movement ranges.

When a mecha hits with an attack they deal variable damage based on their damage die. Specific weapons simply provide bonuses such as extra chances to hit, more damage or additional abilities on a strike, a Heavy Ranged Weapon for example gives +2 to attack and damage whereas weapons with the ‘Arc’ property can force enemies to lose turns. This is a good way to represent a ‘fighting’ class being more effective in combat than a ‘scouting’ class. A roll of a ‘1’ is a critical success and a ‘20’ a critical failure within the system. A critical success deals double damage, whilst a critical failure on a roll to avoid an attack means you take double damage.

When a player controlled mecha reaches 0 HP it is disabled, it cannot take actions and fails all tests until repaired. It also has to roll on the Disabled Mecha table which produces results that range from being entirely destroyed, to permanently losing modules to being hobbled and having disadvantage on Mobility tests specifically. The game as a result is still quite lethal but the 'buffer' of having a robot as your character means you can more easily find ways to get it to repair than you normally can raising a dead character in a trad fantasy game.

Armour works in a similar way to The Black Hack or Mork Borg in that it reduces damage. You can spend a number of armour points and reduce damage you’ve taken by that amount but must rest to regain them. If you lose all of your armour then you have to take damage as normal. In many ways this method of armour works better in a mecha game than a fantasy one at least in a narrative sense as they represent your tarmour being chipped away throughout combat and other dangerous scenarios. Or perhaps most RPG players are just more familiar with static rather than variable armour systems.

Resting uses a short rest/long rest system familiar to players of 5E D&D as well as of course The Black Hack of which it derives. A short rest is an hour and allows you to regain your armour points as well as one hit die worth of hit points up to your maximum. A long rest is considered eight hours or more and lets you regain all of your hit points and raise your reactor die to max. This is intended to represent you making major repairs or mods to your mecha and then sleeping for a few hours. As written this can be done in the field, though some GM’s may say it’s only allowed in a Mech Bay or equivalent repair area.

The Mecha Hack comes with a ‘bestiary’ of foes that include everything from Jump-Pod equipped mecha, to anti-mecha hover tanks to gigantic Kaiju or spider mecha armed with immense thunder cannons. The game certainly isn’t shy about including the huge and silly elements of ‘mecha’ lore rather than say the relatively more realistic tone set by games such as Battletech but also provides enough for the GM to be able to craft the type of ‘mecha’ world they want. These NPC’s all have unique profiles detailing their hit die, special abilities and how much damage they deal on their various attacks, working in a simplified manner compared to player mecha.

Standard hit die for enemies is d8, meaning a 1 HD foe will have 8 hit points at maximum but the GM can roll for their hit points as well. This d8 HD mirrors the amount an NPC in Moldvay Basic D&D would have and is an increase on the d6 that original D&D assumed. Damage is variable and based on the HD of the enemy with a HD 1 enemy dealing 1d4, a HD 4 enemy dealing 1d10 and a HD 10 enemy dealing 2d12.

Advancement is through a levelling system that effectively works as milestone levelling in 5e D&D.

When your mecha overcomes significant obstacles and foes the GM can give them a ‘level’. This is purely up to GM discretion and differs significantly from the original & basic D&D method of levelling based on experience points with every gold piece you find giving you one experience as well as monsters you overcome giving you experience. This method however does seem to suit a mecha game which is going to be likely more focussed around characters completing set missions rather than actively exploring environments such as dungeons or the wilderness in search of treasure for long periods of time as in old school D&D.

Levelling lets you increase your max HP by your hit die just as in original & basic D&D. At level 3, 6 and 9 you can also choose new modules for your mecha with the maximum level capping at 10. You can also uniquely directly increase your attributes, you roll a d20 for each and if you roll higher that value increases by one. Most OSR systems don’t include direct ability improvement as part of levelling as it wasn’t a thing in original or basic D&D beyond magical means. Though it is a feature in 5E D&D which allows you to increase attributes at certain levelling intervals.

It’s not all combat either. There’s rules for ‘skill challenges’ which were in 4th Edition D&D and allow a group to overcome non-combat situations through a collective series of decision making and die rolls based on their character abilities. There’s also rules that cover dealing with environmental hazards as well as Pilot and downtime activities and even dealing with the fallout of collateral damage that your mecha may cause in the field to civilian structures and habitats.

One huge aspect of a mecha game is customisation and whilst The Mecha Hack doesn’t provide an extensive list of options it does offer a solid variety of means to customise your mecha in between missions. You can upgrade and change their weapons and armour and refit them with different modules that have a variety of effects. There’s also encouragement for the GM and players to come up with their own custom modules and mecha customisation rules of their own creation.

There’s a whole bunch of fluff at the back of the book which whilst not extensive given the entire booklets 48 page size provides enough information about the world, its history and the various factions and interesting locations within it to give the Game Master alongside the various random tables enough information to start running sessions of the game.

Overall The Mecha Hack is a sublimely clean and well designed example of how to take the core of a roleplaying game and ‘hack’ it into something else entirely that still fits. It’s an incredibly simple and quick game to set up and run with just enough crunch to make it satisfying as a mecha game. It demonstrates the flexibility of The Black Hack as a system as well as the overall flexibility of the ‘OSR’ genre of games in allowing you to run a wide array of genres within them that go beyond classic fantasy.

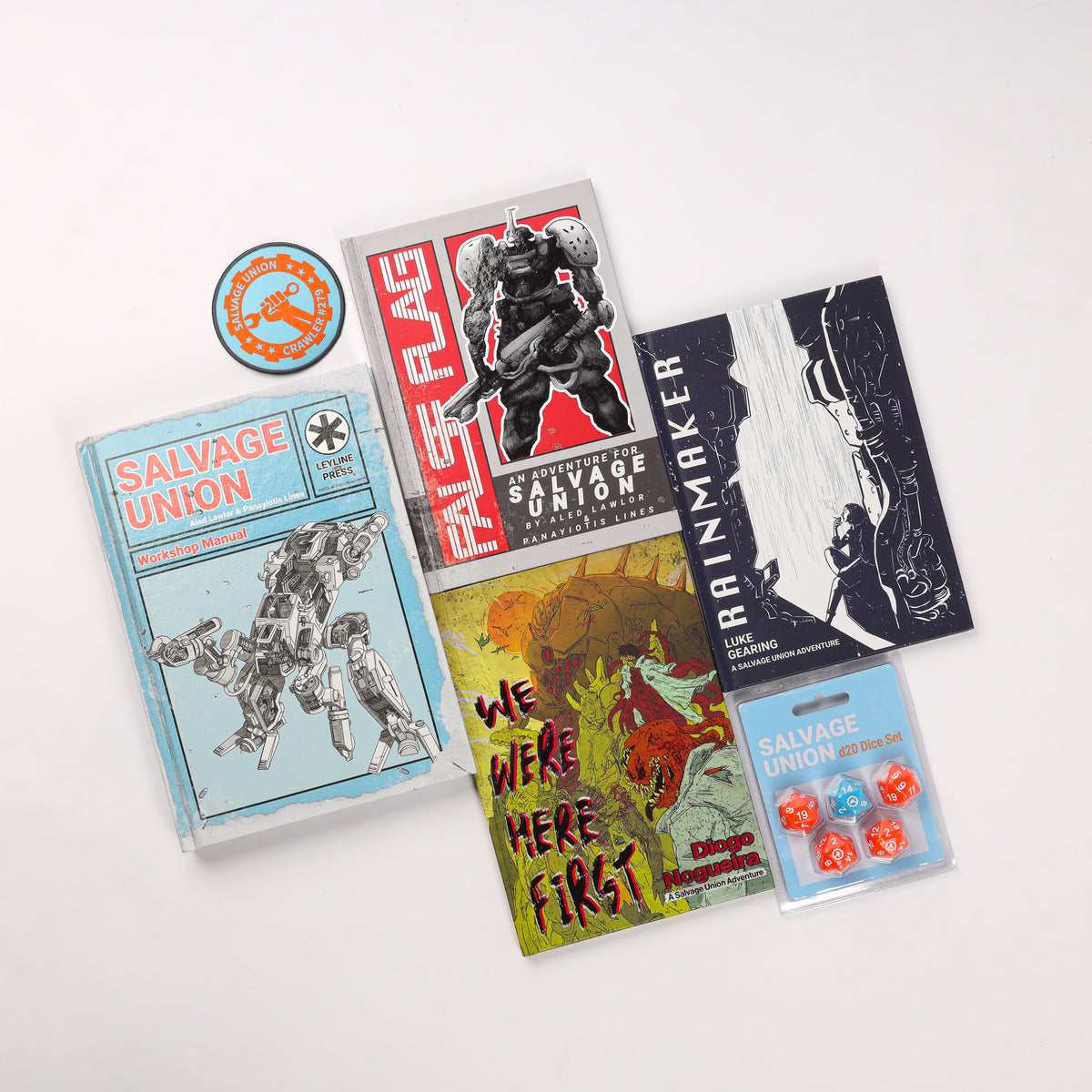

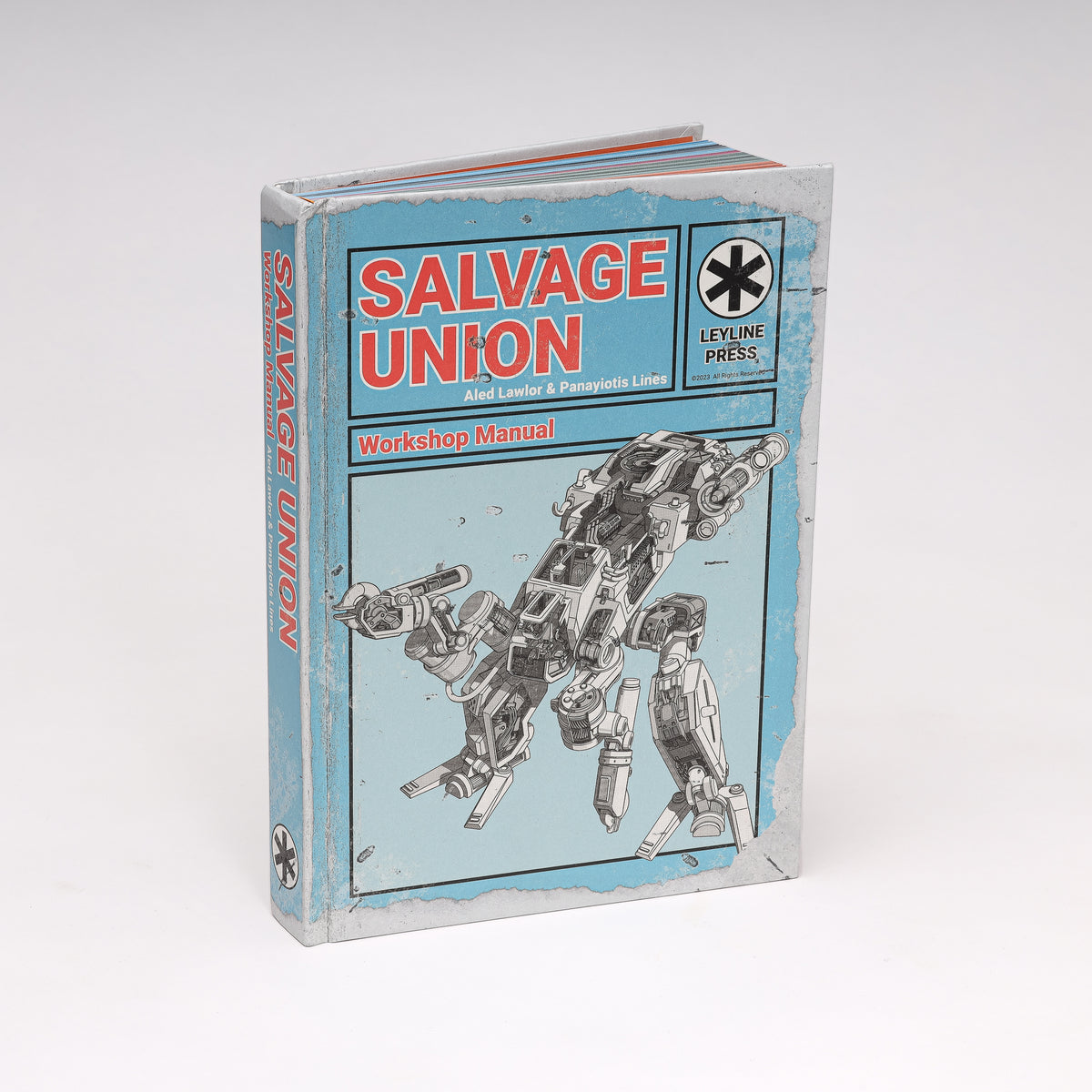

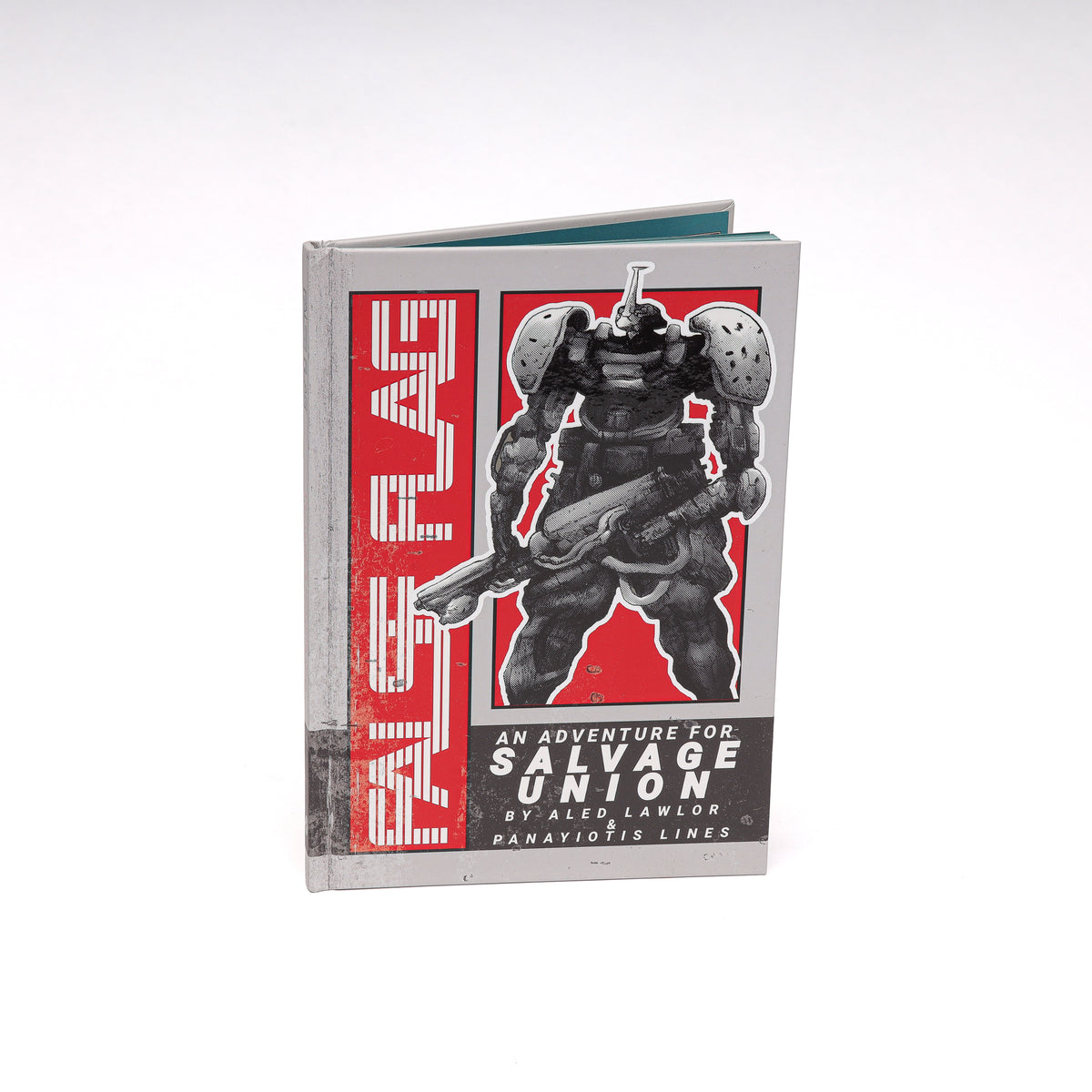

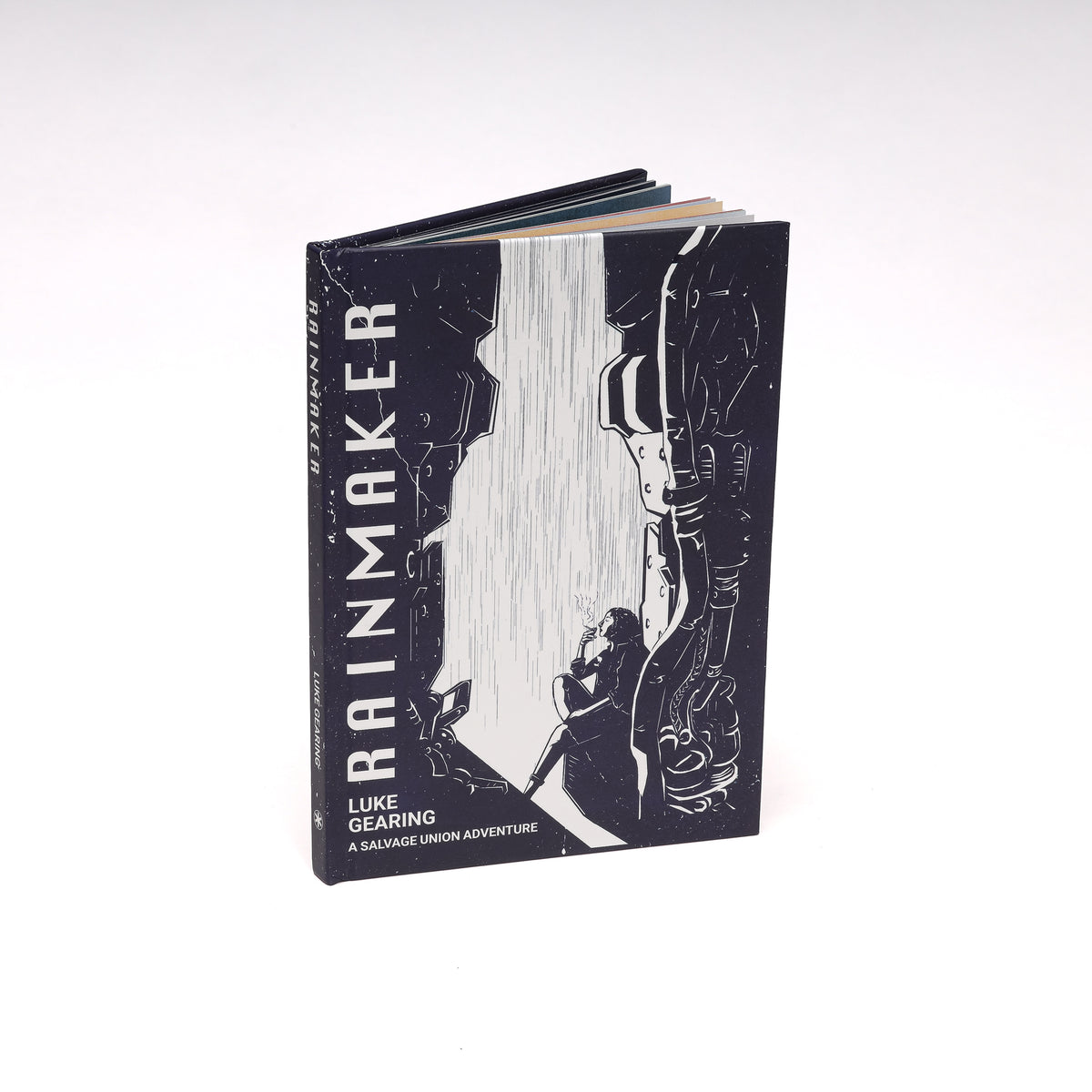

Interested in Mech TTRPG's? Check out Salvage Union, a post-apocalyptic mech game powered by Quest, now available to buy here.

You can explore our old school adventures here.

Subscribe to the Leyline Press newsletter here to receive updates on our blogs, promotions, games and more.

Follow us on twitter @leylinepress

Follow us on facebook @leylinepress

Follow us on instagram @leylinepress

Follow us on tiktok @leylinepress

Subscribe to this blogs RSS feed by pasting this into your feed reader - https://leyline.press/blogs/leyline-press-blog.atom

0 comments