In this first article we’ll be looking at 0E D&D the game that started it all.

‘0E’ Dungeons & Dragons refers to the original edition of Dungeons & Dragons published in 1974. This was written by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. OD&D came in a white box set and is sometimes referred to as ‘White box D&D’. It splits into various different rules booklets. Men & Magic, Monsters & Treasure, and Underworld & Wilderness Adventures as well as a Reference Sheets. These cover a wide array of different rules and aspects of the game.

OD&D derives many of its rules from the earlier medieval miniature wargame ‘Chainmail’ that Gygax had created and released in 1971 along with Jeff Perren. The rules assumed knowledge of Chainmail in many places such as the combat rules. OD&D also drew inspiration from Avalon Hill’s board game ‘Outdoor Survival’, especially via it’s wilderness exploration and hexcrawl rules. It was a mash up of various different games, systems and ideas as a result.

The core D&D premise of OD&D is a simple one that would remain relatively unchanged throughout the various editions of the game to come. You create a character, whether a noble fighter or mystical Magic-User and play as them within a medieval fantasy world alongside a group of other players. You choose what they say and do whether to tell a lie to a city guard about why you are in the city or sneak past a group of bandits on the road. One player acts as the Dungeon Master who is responsible for running the world, creating situations within it and acting out the roles of everyone else in the world from the village tavern keeper to a monstrous Troll. Dice are often rolled to resolve situations such as what happens when you try to attack an Orc with a sword or sneak through a castle but the Dungeon Master can also rule situations themselves based on context.

When creating a character you roll 3, six sided dice for each of the six ability scores in the game. These 6 ‘core’ statistics of Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Wisdom, Intelligence and Charisma would be in the game to this day. Each of these stats would grow into a life of their own and was meant to represent different aspects of your character, however the main thing they did within OD&D was determine your Prime-Requisite.

The Prime-Requisite was the core stat each class was intended to use. Fighting-Men had a Prime-Requisite of Strength, whilst Magic-Users used Intelligence. The main thing this did was boost your experience points if your prime-requisite was high enough by 5% or 10%. Which meant good characters got better faster, an early form of ‘Gygaxian Naturalism.’ This refers to an attempt to create a ‘real’ world and ecosystem within it built out of a set of assumptions. In this case, if you’re good at something you’ll get better at doing it more quickly, reflecting what we know can be the case in reality. This type of design would be seen throughout Dungeons and Dragons. However beyond the Prime Requisite the ability scores didn’t do huge amounts by the rules beyond a few token bonuses here or there.

After rolling abilities you picked a character class which defines what your character is good at doing within the game. The 3 core classes in OD&D are ‘Fighting-Men’, Cleric and Magic-User. The Thief as well as the Paladin would be introduced soon after in 1975 within the Greyhawk supplement.

Fighting-Men are good at fighting, they have more health than the other classes, hit more easily and can wear all weapons and armour. Cleric’s have the ability to cast holy spells drawn from their god that can heal allies, purify food and detect sources of evil. They also have the ability to cause undead creatures to flee from them. They are banned from using edged weapons as well, mirroring a myth that medieval clerics couldn’t use edged weapons. This would be the first of many rules within the game that would force players to play a specific archetype when running a character of a certain class.

Magic-Users would be fragile and progress slowly but have access to a wide range of magical spells that could do everything from force enemies to go to sleep to shoot fireballs. The Thief would have a wide range of abilities that would let them detect and disable traps, sneak around silently, climb sheer surfaces and pick pockets among other things.

The Paladin was a sub-class of the Fighter, they required a Charisma score of 17 to play and were always of a Lawful alignment. They could lay on hands to cure wounds and diseases and were immune to disease themselves. However they could lose their powers if the player did not play them in a ‘Lawful manner’ based on the game’s loosely defined alignment system.

You can also play as an Elf, Dwarf or Hobbit as well however these are all technically ‘sub-options’ of the ‘Fighting-Men’ class. The Elf can fight as well as cast magic spells able to take levels in either Fighting-Men or Magic-User. The Dwarf has better saves against magic and other effects and can spot slanting passageways, traps and shifting walls. The Hobbit gets a bonus to missile weapons as well as improved saves.

The game had a magic system based on the Dying Earth books by Jack Vance. This would come to be known as Vancian magic. Within this world spellcasters would have the ability to memorise lists of spells then would forget them when they were cast. The spells would also have idiosyncratic names based around the spellcaster who created it such as Phandal’s Mantle of Stealth. D&D magic would mirror this, spellcasters got a small list of spells they could memorise and casting them would spend them until they could prepare them again which would typically require a night’s rest. There were also spell names such as Bigby’s Magic Hand and Mordenkainen Magnificent Mansion that would be later introduced to D&D and were based around characters such as Mordenkainen who was in Gygax’s own home campaign.

It’s amusing how the magic system that has been used throughout the game’s history and remains today in a limited form was put in place mostly as Gary Gygax really liked the Dying Earth books. It could have easily used a spell point system or some kind of mana system, or anything else. D&D came together as a frankenstein monster of many parts that seemed to work almost as accidentally

There’s an extensive list of magic spells available as well as monsters and treasure and the core gameplay ‘goal’ of finding treasure to gain experience points is within this edition. For each gold coin players would find their characters would gain one experience. This would be the main way to advance and is what makes games of original D&D engaging. The game isn’t about murdering the monsters, it’s about finding your way to the treasure with whatever plan you and your group can come up with. This encourages exploration and creative play.

Each class grew in power but at different rates and with different limits. Dwarves for example were limited to only getting to 6th level, whilst Fighting-Men could in theory advance to any level. It took 2,000 XP for Fighting-Men to advance to 2nd level and 2,500 for a Magic-User. This was intended as a form of game balance, the Magic-User grows incredibly powerful as the game progresses but starts off weak and must earn more experience to progress. The Dwarf is stronger in many aspects to the base Human Fighting-Men but has a limit to how far they can progress.

OD&D has a flat curve to it’s maths, for example any score of 13-18 in Dexterity will provide a simple +1 to hit using ranged weapons. In comparison within B/X D&D a 13-15 provides a +1, a 16-17 a +2 and an 18 a +3. All weapons in the game do a flat d6 damage as well, whether great axe or dagger, and most monsters have hit die in d6’s. This means that one hit with any weapon will kill most level 1 characters or monsters.

The flat math echoes the game’s wargame roots where large numbers of units would clash against one another meaning and one secret of OD&D, as well as most OSR D&D editions is that they make resolving large scale warfare relatively simple.

OD&D would introduce the games alignment system of Lawful, Neutral and Chaotic inspired by the novel Three Hearts and Three Lions by Poul Anderson. You would choose one of these alignments for your character when you created them and they could shift as you made decisions within the game.

Within the novel the forces of Law and Chaos fight an endless war with one another whilst the common folk ‘neutral’ lie in between. Whilst simplistic this encouraged players to roleplay their characters towards one axis or another and provided reason for conflict with Lawful characters desiring to stop the deeds of Chaotic characters. The alignments were also game relevant, with Chaotic characters being able to hire mercenaries such as Orcs and spells such as reincarnation turning characters into different creatures based on their alignment. Each alignment also had a language allowing characters to speak to one another in it if they were of the same alignment.

Encumbrance and weight of equipment would be introduced in this game and remain an important factor throughout D&D. Weight would be measured in ‘coins’ with 1 coin equal to 1/10 of a lb in weight. So an average man weighing 175 lbs would weigh 1,750 coin weight. Leather armour in the game would weigh 250 coins.

Characters would be slowed down if they had too much gear which would make journeying through dungeons and the wilderness a slower affair, meaning more chance for random encounters. Whilst unintuitive at a glance, coin encumbrance t did allow you to quickly add up the value of both your coins and your equipment and tied into the games core goal of finding treasure. Gems for example would be particularly valuable treasure as they weigh significantly less than their coin value, whereas if a group found 100,000 copper pieces that 1,000 gold of value would be spread into a vast amount of weight for them to work out how to carry out of the dungeon.

OD&D has many idiosyncratic rules, contradictions and omissions which are spread often incoherently through the text. It’s effectively a hodge podge of different house rules and game systems combined into a set of books and makes a lot of assumptions that either the reader was expected to know being familiar with wargaming or that the authors simply knew but didn’t care to tell the reader.

There’s highly specific rules in the text to cover relatively niche situations such as encountering a ‘fighting-men’ stronghold and being challenged to a joust. However rules for what the core Strength stat does are left rather vague. The entry notes ‘Strength will also aid in opening traps and so on.’ Players are also given the option to play as a monster but with no rules to govern how. Whilst monsters such Gnolls were actually described as a hybrid cross between a Gnome and a Troll which is rather delightful. Two entirely different combat systems are suggested, one drawing from the Chainmail miniature rules set and one using initiative, attack rolls and damage.

This isn’t inherently a bad thing, the rules light nature of the game allows players to be flexible and creative and for the GM to interject their own rules to the game. The game almost begs to be refined and house ruled by whoever is running it to make it a lot more clearer and concise.

The Holmes Basic edition of D&D would come to do exactly that which we’ll discuss in the next article here.

Thanks for reading! If you're interested in a trio of old school fantasy adventures check out Albion Tales.

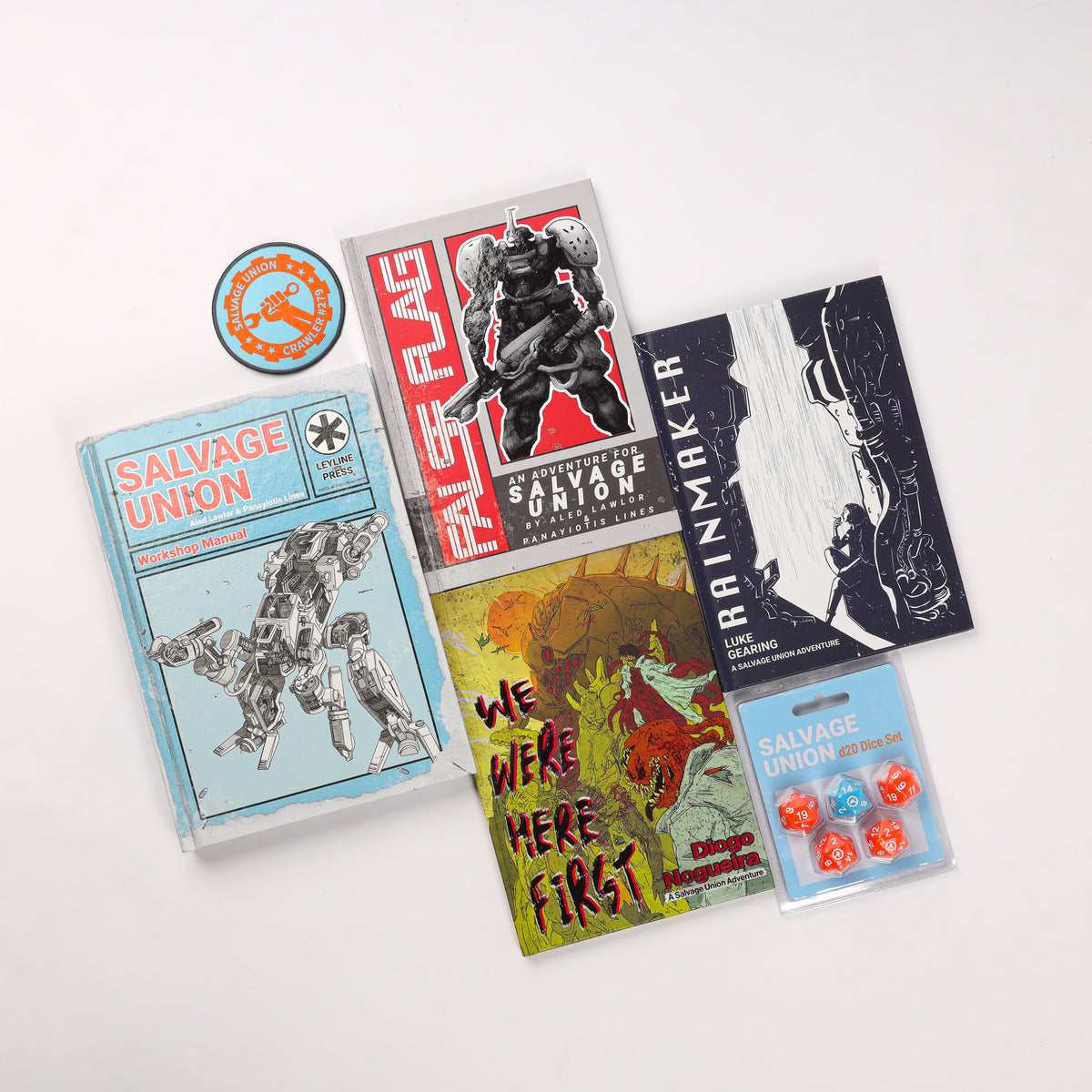

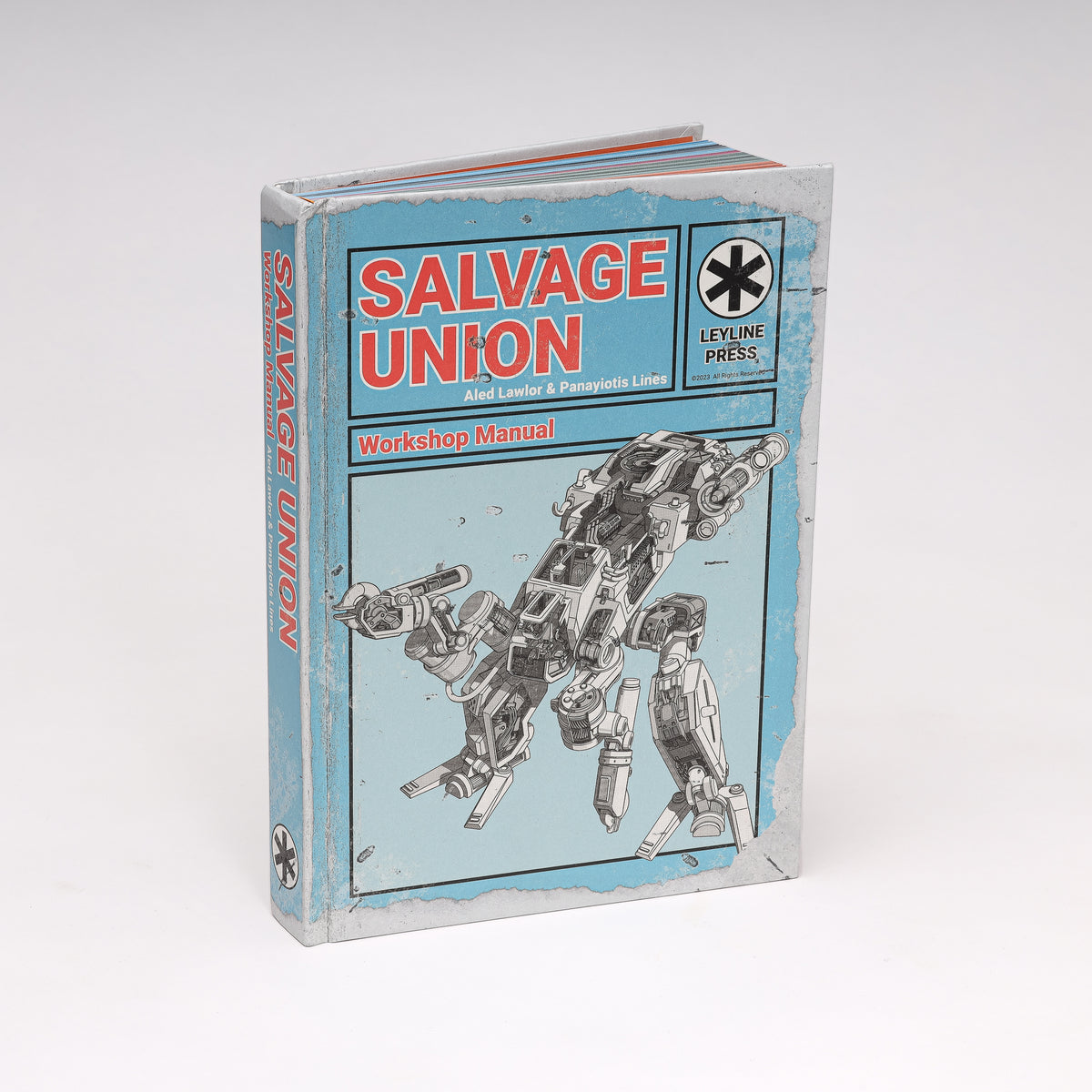

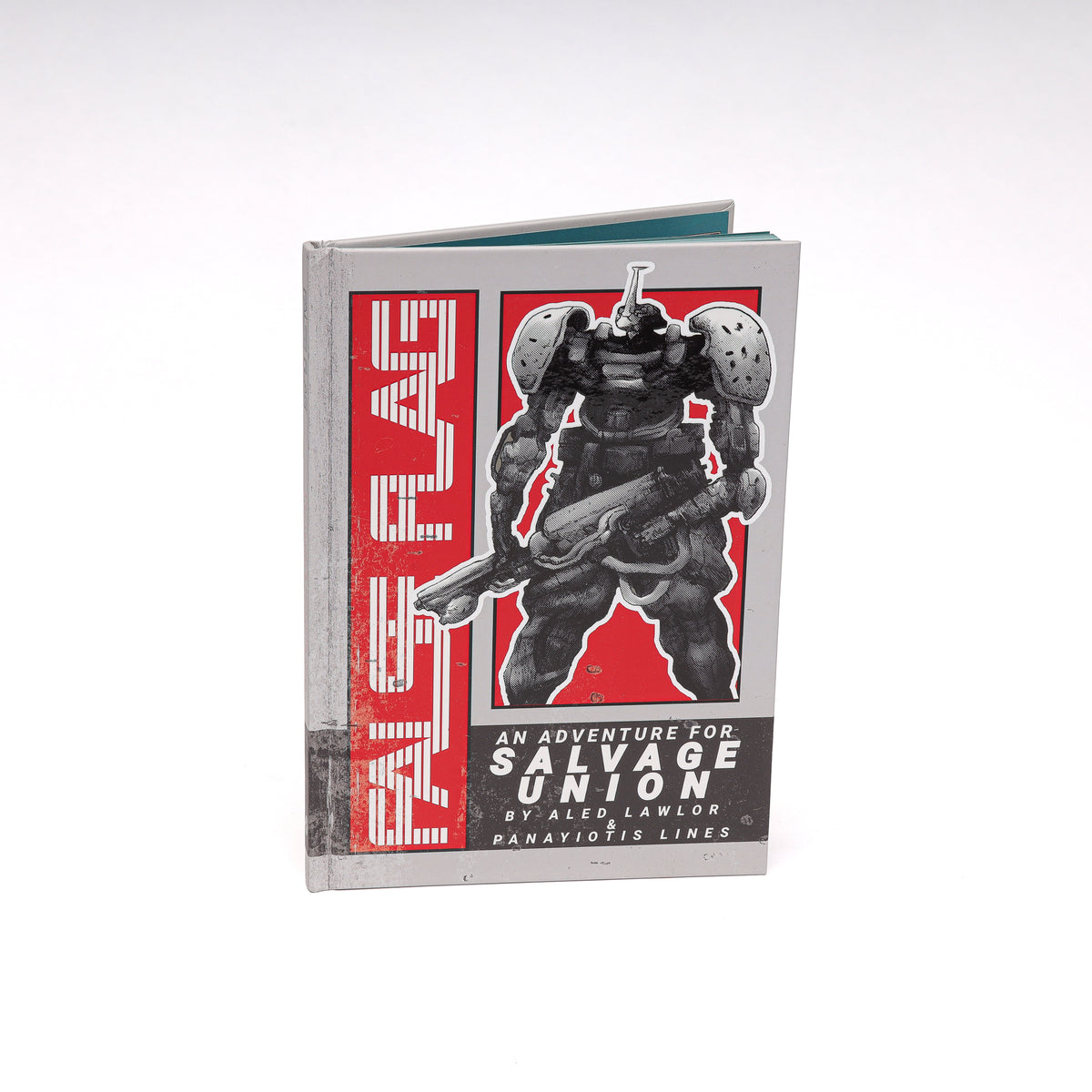

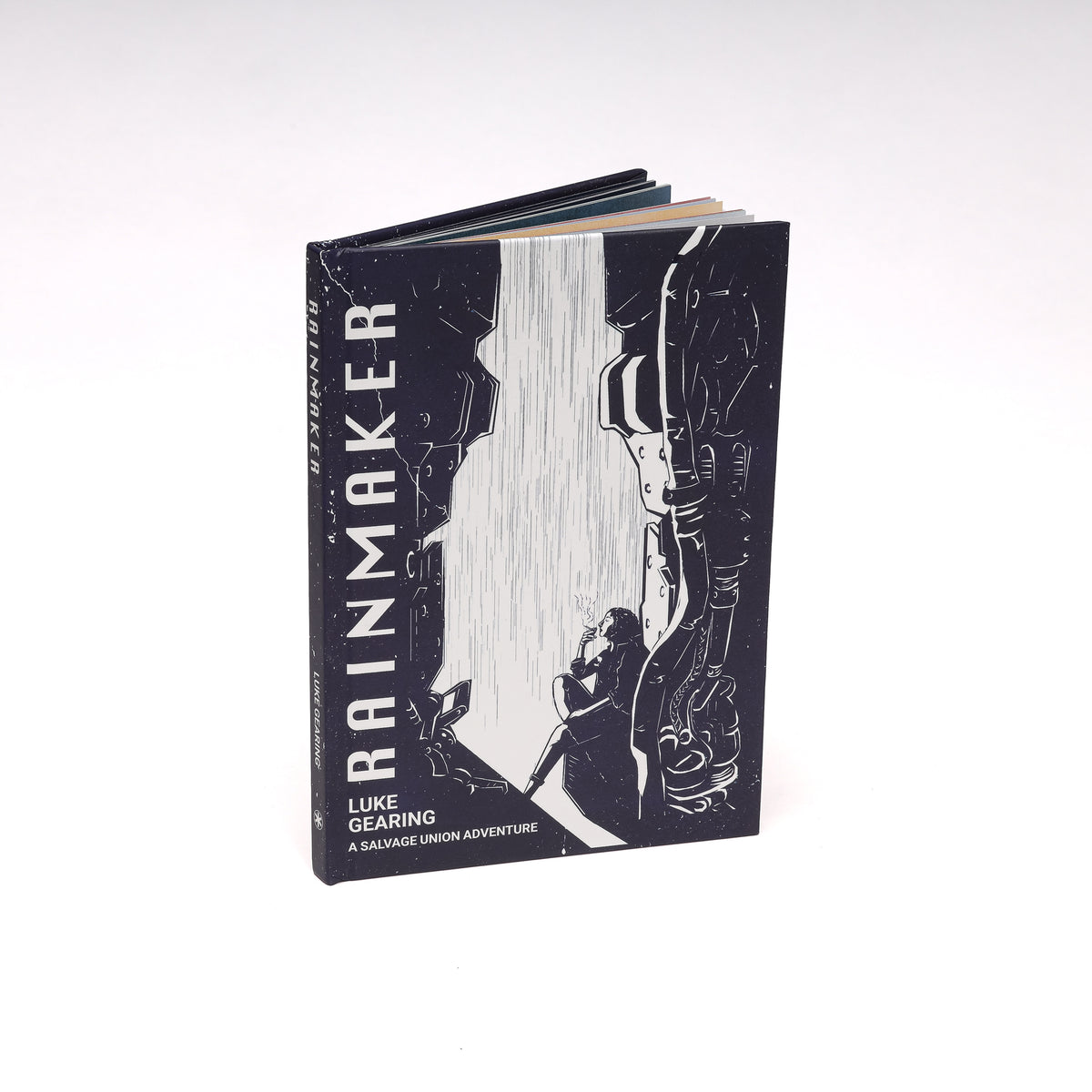

Subscribe to the Leyline Press newsletter here to receive updates on our blogs, promotions, games and more.

Follow us on twitter @leylinepress

Follow us on facebook @leylinepress

Follow us on instagram @leylinepress

Subscribe to this blogs RSS feed by pasting this into your feed reader - https://leyline.press/blogs/leyline-press-blog.atom

This article was originally written for https://www.osrelfgame.com/

0 comments