In this series of articles we'll be exploring the differences and similarities between every edition of Dungeons and Dragons.

In the last article we looked at BECMI D&D which you can read here.

In this article we are looking at AD&D launched in 1977.

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was first published in 1977 and served as an ‘advanced’ and ‘definitive’ version of Dungeons and Dragons for players to play who had graduated with the ‘basic’ set.

The game split into the iconic 3 books, The Players Handbook, The Dungeon Master Guide and The Monster Manual. This pattern has stayed the same for D&D to this day.

The Players Guide is a lot lighter than in modern editions of D&D at about 127 pages. It contains all of the rules for creating characters as well as some information about spells, combat, weapons, hirelings and useful advice on playing the game. However many of the core rules for the likes of combat, spell casting or wilderness and dungeon exploration are either missing or not properly fleshed out. These are contained in the Dungeon Master Guide instead.

This was a purposeful design decision that kept much of the core information of how the game works in the hands of the Dungeon Master. The idea was that to create that feeling of discovery in play the players should be presented with the situation itself and not know the finer rules points of how it would play out so they react naturally rather than based on a 'meta' rules knowledge of the situation. It also keeps the game fresh and full of surprises if the players can't read about the monsters, traps, tricks or magic items within the game.

Gygax feels really strongly about this and writes in the preface to the AD&D DMG

"As this book is the exclusive precint of the DM, you must view any non-DM player possessing it as something less than worthy of honorable death. Peeping players there will undoubtedly be, but they are simply lessening their own enjoyment of the game by taking away some of the sense of wonder that otherwise arises from a game which has rules hidden from participants."

This contrasts heavily to Wizard's of the Coasts attitude. Within the 5E Players Handbook all the of rules are laid out bare. This emphasises far more power in the hands of the players to build and customise their characters but has the negative effect of spoiling the game and encouraging 'power gaming' / 'min-max' play which is born out in all of the numerous optimisation forum where every single character option is compared and contrasted with all the other possible monsters or situations a group might encounter to find the 'best' ones.

Granted the internet exacerbates this and no doubt players powergamed with AD&D as well, simply telling someone to not read a book doesn't stop them doing so after all but WOTC have certainly leaned into that new crunch and player focussed design space and abandoned the idea that many elements of the game should be kept secret from the players and just be within the purview of the Dungeon Master.

Granted the internet exacerbates this and no doubt players powergamed with AD&D as well, simply telling someone to not read a book doesn't stop them doing so after all but WOTC have certainly leaned into that new crunch and player focussed design space and abandoned the idea that many elements of the game should be kept secret from the players and just be within the purview of the Dungeon Master.

The 5E DMG is the sidenote in the current release with many Dungeon Masters not even purchasing the guide or reading it as everything you need to play is in the Players Handbook.

The AD&D Players Handbook is different in tone in this respect, in many places it's written directly to the player, it not only explains the rules but explains how you are meant to 'play' . For example in the 'Negotiation' section on page 104 of the AD&D PHB

"As a player, you must earn what you gain. Negotiation usually gives you a chance to get on with the earning process, or live to come back and fight another day. Always be wary and use your wits, look at all facets of the situation and then use your best judgement accordingly."

This sort of direct advice to the player is incredibly useful especially in the context of the 1970s where most people really didn't have a grasp of how a roleplaying game was meant to work, it also feels quite personal like words Gygax would tell you himself at the table if he were running a game for you.

The Dungeon Master Guide is written in this style as well but aimed towards the DM. It's probably one of the best guides to running a roleplaying game campaign ever written with a wealth of advice that is not only useful for D&D but broadens to other games too.

Beyond the fleshed out rules there's lots of advice on simply managing the group and player expectations. This is pretty 'normal' now but back then served to really explain in detail how the game was meant to work and how to deal with the various interpersonal issues that inevitably arise from running a game. These include how to host a game, how to handle troublesome players, how to integrate a new player into an existing group, when and who should roll dice in certain situations and what to do if a player wants to play as a monster.

The Monster Manual would includes a huge variety of now iconic D&D monsters from Basilisks to Bugbears to Bulettes. These are of courses statted with the updated AD&D rules and fleshed out further with information on their ecology and habits, there's a lot more artwork in this book than ever before with a wide range of the monsters in the book given art along with rules. For it's time this was a 'premium' roleplaying book, full hardcover and packed with a multitude of monsters to use at the table. Much of the art is quite quaint by todays standard but the fact it had so much of it was impressive for a roleplaying game product at the time.

AD&D contains significantly more rules than Basic D&D to cover a myriad of different situations. It's rules are ‘fragmented’ in the sense it doesn’t have an explicit core mechanic but instead has different rules for different situations. There’s everything from what to do if the party sieges a bandit camp, to the effects of drugs and alcohol, to the lists of classes, equipment and monsters you’ll find in Basic D&D but with far more detail provided.

It still contains the same core of D&D rules on how to run dungeons, wilderness exploration, create characters, and describes equipment, spells and combat. However additional exhaustive detail is added by Gary Gygax to flesh out all of these concepts with more crunch and detail.

Gygax aimed with AD&D to create a 'definitive' version of D&D, a shift in design philosophy from basic which set its rules out as more of a modular toolkit for the referee and group to use. Written in the preface of the AD&D DMG he writes

"You must avoid the tendency to drift into areas foreign to the game as a whole. Such campaigns become so strange as to be no longer AD&D.... "

"Imaginative and creative addition can most certianly be included; that is why nebulous areas have been built into the game. Keep such individuality in perspective by developing a detailed world based on the rules of ADVANCED D&D.

These two quotes make it pretty clear that Gygax is saying AD&D is D&D and anything else outside of it , whether in respects to world building or rules is no longer Dungeons and Dragons. This is somewhat ironic considering the AD&D module Expedition to Barrier peaks has players exploring a literal spaceship which is rather a genre shift. In general this is also a change in Gygax's attitude towards the game and those running it.

Within OD&D in contrast it's written that a player can play as anything they like, even a Dragon is possible with the right adjustments, but within AD&D it's emphasised that they should stick to the core races in the AD&D books for the most part and monster races should be a no. In modern D&D monster races are the norm and WOTC go to effort to stat them out as player races, allowing players to play anything from Tieflings to Tortles to Tabaxi.

One could argue this shift was so that Gygax could keep his own creative vision of the game alive and prevent it being turned by the players into something that he didn't want it to be. Indeed the 'Deities and Demigods' supplement released in 1980 was quite explicitely created when Gygax and others at TSR realised referees were letting players 'too easily' crush gods such as Odin in their games and wanted to create a definitive source of what a god like being should be statted as.

However from a more cynical perspective, it also let Gygax take control of Dungeons and Dragons and sell it effectively as his and TSR's intellectual property. By stating AD&D was D&D and everything else was no he was laying claims to the game and what boundaries it should exist within. This model still persists today, though WOTC focus towards the players now rather than the referee they still use the same top down model and by creating such a wealth of layered rules and tying it into their community lay claim to the game and discourage groups and DM's actively changing the rules or doing their own thing.

This shift in the rules and design philosophy also let Gygax and TSR attempt to shove Dave Arneson out of his royalities by claiming AD&D was such a different game from OD&D that the original royalty contract they had signed was void. Gygax would repeatedly lose this point in court but the design changes certainly let him try and pointed towards the game becoming far more of a packaged product than a toolkit

Back to the meat of the rules, the core 6 ability scores remain but are expanded out in scope. For example the Strength table allows you to cross reference your Strength ability score to determine your hit probability in combat, your combat damage bonus, your weight allowance, your ability to open doors and your ability to Bend Bars and Lift Gates.

Ability scores in AD&D could also go past 18 but were subdivided into percentile sections. So a character with 18 strength would roll a d100 and their strength could range from 18/01-50 to 18/00. This peak of ability however was only available to male human fighters, one of the rare examples of D&D rules discriminating on gender in an effort of ‘simulationism.’

One significant change from Basic is that Race and Class are now split in AD&D rather than Race and Class being the same thing. This means that you can play as a Dwarf Cleric or a Halfling Thief. There were still limitations in this respect, a Halfling could never be a Cleric and a Dwarf could never be a Magic-User. Humans still had the ability to play as any class solidifying their ‘flexibility’ as a choice. The Half-Elf, Half-Orc and Gnome were also added to the race list in AD&D.

The core classes of Fighter, Magic-User, Thief and Cleric remained however a host of new classes were introduced as well. Additional AD&D classes included the Bard, Druid, Psion, Paladin, Ranger, Illusionist, Assassin and Monk. Many of these would have fairly stringent requirements in terms of both statistics you needed to play them and roleplay you needed to adhere to and they’d technically be ‘sub-classes’ of pre-existing classes.

The Paladin, a fighter subclass designed around the archetype of a holy warrior, now requires a Strength of 12, an Intelligence of 9, a Wisdom of 13, a Constitution of 9 and a Charisma of 17.

A Paladin must also always be of a Lawful Good alignment and if they do not act in such a manner they risk losing their range of Paladin abilities. Many of these abilities are very powerful including the ability to detect evil, improved saves, immunity to all disease and the ability to lay on hands to heal allies.

It can seem rather arbitrary that a player who simply rolls well enough to be a Paladin gets to be one and gains many powerful abilities to boot, however a group with a Paladin would create an entirely different experience of play. Their rarity would also make them rather a novelty as well. ‘Gygaxian Naturalism’ is at play again here, the rarity of Paladins within the world is reflected by the rarity of Paladins at your gaming table. A group with a Paladin is something unique to tell tales about.

Within modern D&D play anyone can play as a Paladin, or anything else, and as such esoteric classes ironically become far more mundane and mundane classes such as Fighter become far more esoteric.

Speaking of alignment, AD&D would implement the now standard '9' pronged alignment where you pick combination of Lawful, Neutral or Chaotic with a combination of Good, Neutral or Evil. This contrasts to OD&D where only Lawful, Neutral and Chaotic were present. Alignment remains in D&D in the same way to this day however mechanics in 5E D&D purposefully avoid caring about alignment and it exists mostly as a popular historical vestiage. In AD&D many mechanics do directly reference it, such as the aforementioned Paladin class and spells such as Detect Evil making it an important game mechanic albeit one primed to cause arguments.

Combat in AD&D would use the base THAC0 system but would be greatly expanded out in detail, initiative would be altered by what weapons your character had and rounds would be broken down into segments. Rules would also be added for the likes of parlaying before a combat, charging, unarmed combat and fleeing. Whilst concepts that existed already such as surprise, reaction and morale in combat would be expanded on with far greater degrees of rules crunch.

AD&D would still use coin weight and encumbrance however would add more simulation esque rules, factoring in the likes of bulk of an item such as armour and adjusting characters dexterity scores if they were carrying too much.

AD&D would retain the Vancian magic system and contain rules for spells of up to 9th level including everything from the Clerics Bless to the Magic-Users world shattering Wish spell. Spells for the new Druid class would be added as well providing a range of nature focussed effects such as entangling enemies in roots. Likewise the new Illusionist class would get access to spells such as Hypnotic Pattern allowing them to hypnotise large numbers of enemies with distracting lights and colours.

The Psionic class was another uniqueaddition to the class roster, modeling an individual with psychic powers and was also an excuse to experiment with a ‘spell point’ ‘magic’ system rather than the traditional Vancian magic system.

TSR would put a lot of resources behind AD&D and many classic modules from D&D’s history were created or re-released around the core of AD&D including Whiteplume Mountain, Against the Cult of the Reptile God’s, Against the Giants and the infamous Tomb of Horrors. The game was hugely succesful and one of the best selling product lines for TSR selling tens of thousands of copies and grossing millions for the company. It was the edition of the game that truly hit as D&D went mainstream.

AD&D would exist up until the late 80s, with many additional books releasing throughout the decade that would contain updated rules for the likes of Wilderness Survival and add more monsters via the Fiend Folio and Monster Manual II.

By the late 80s Gary Gygax had been unfairly ousted from TSR and the company was going in a new direction. TSR wanted to consolidate and update all of the existing rules in order to launch a new product line, aimed towards a younger demographic, that would become AD&D 2E which we will discuss in the next article.

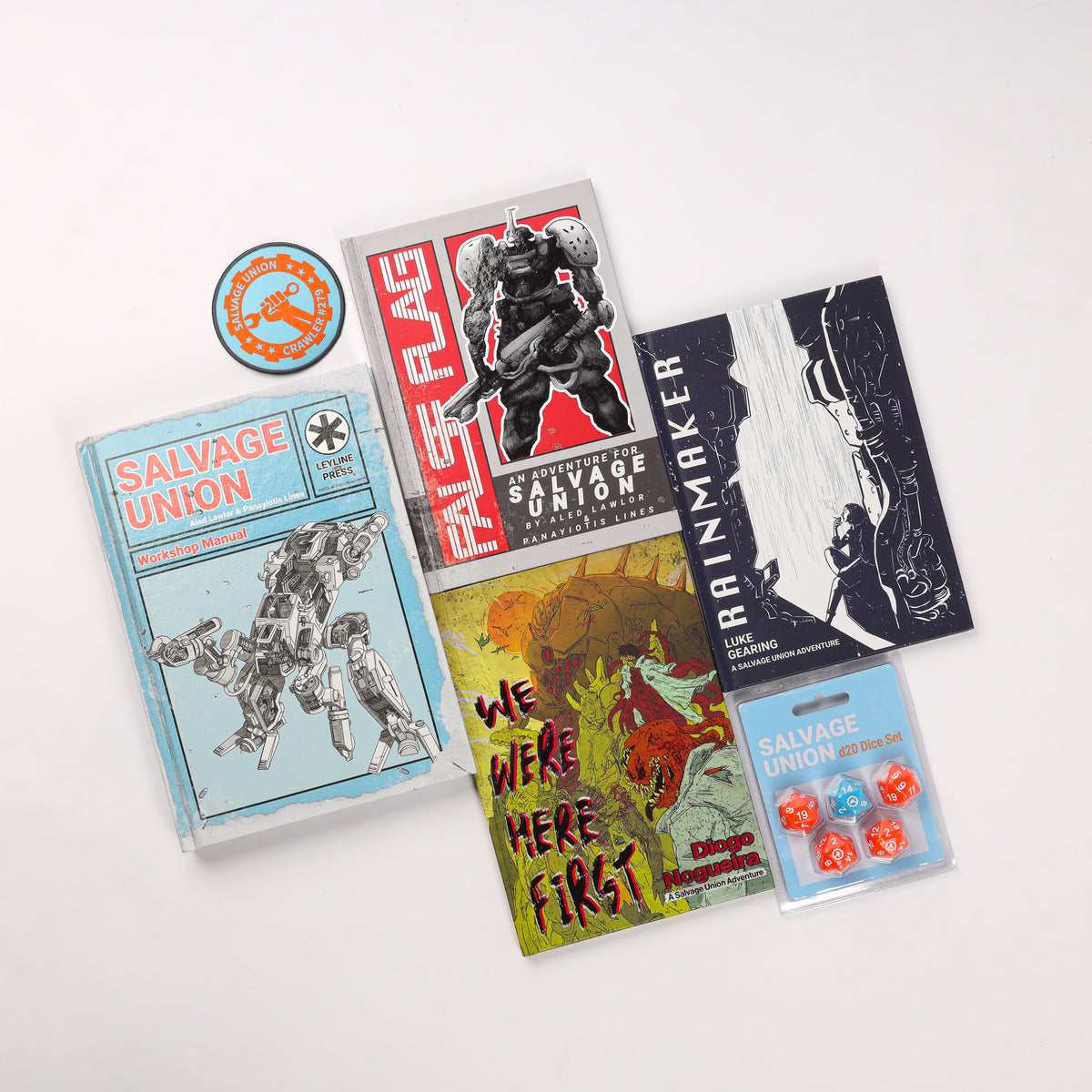

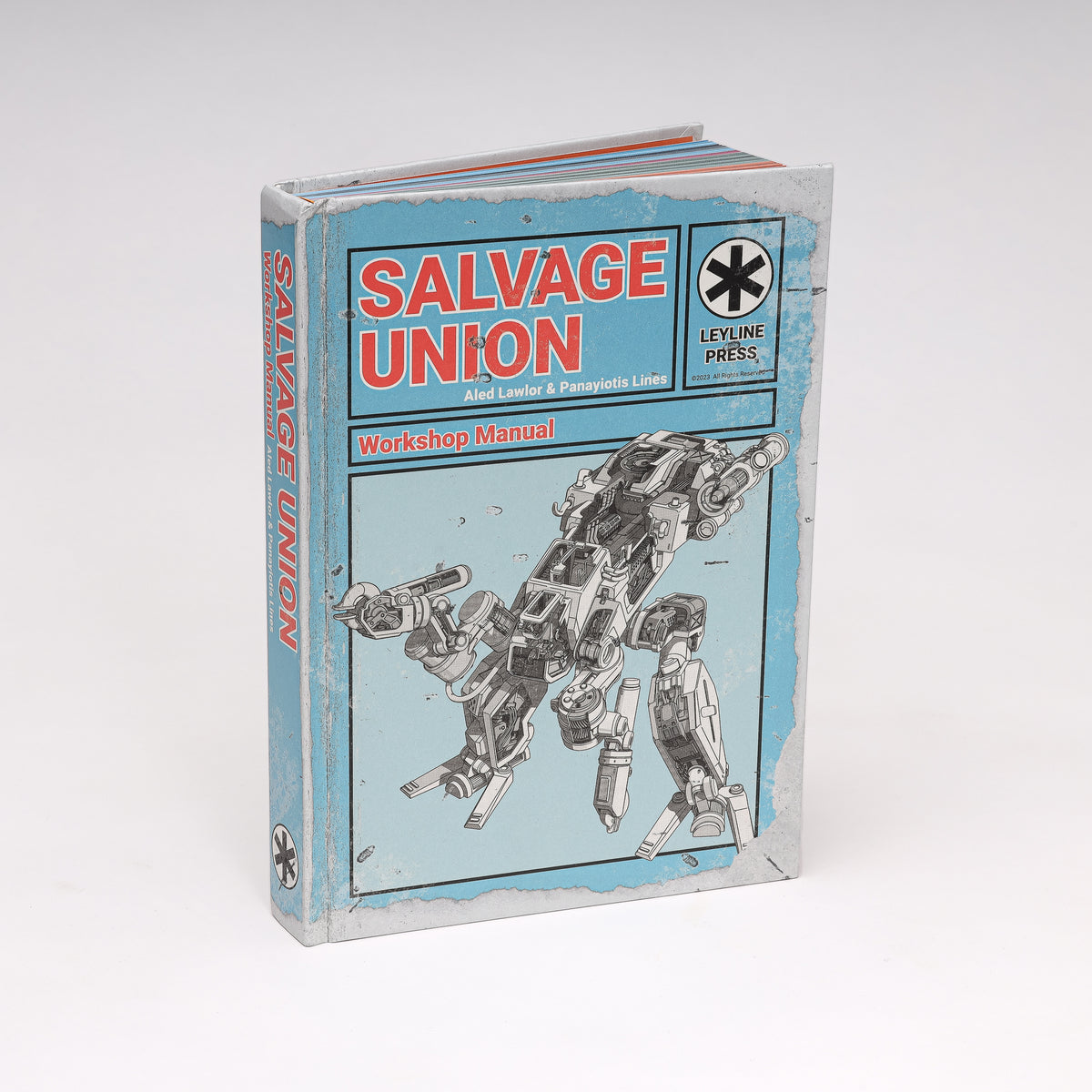

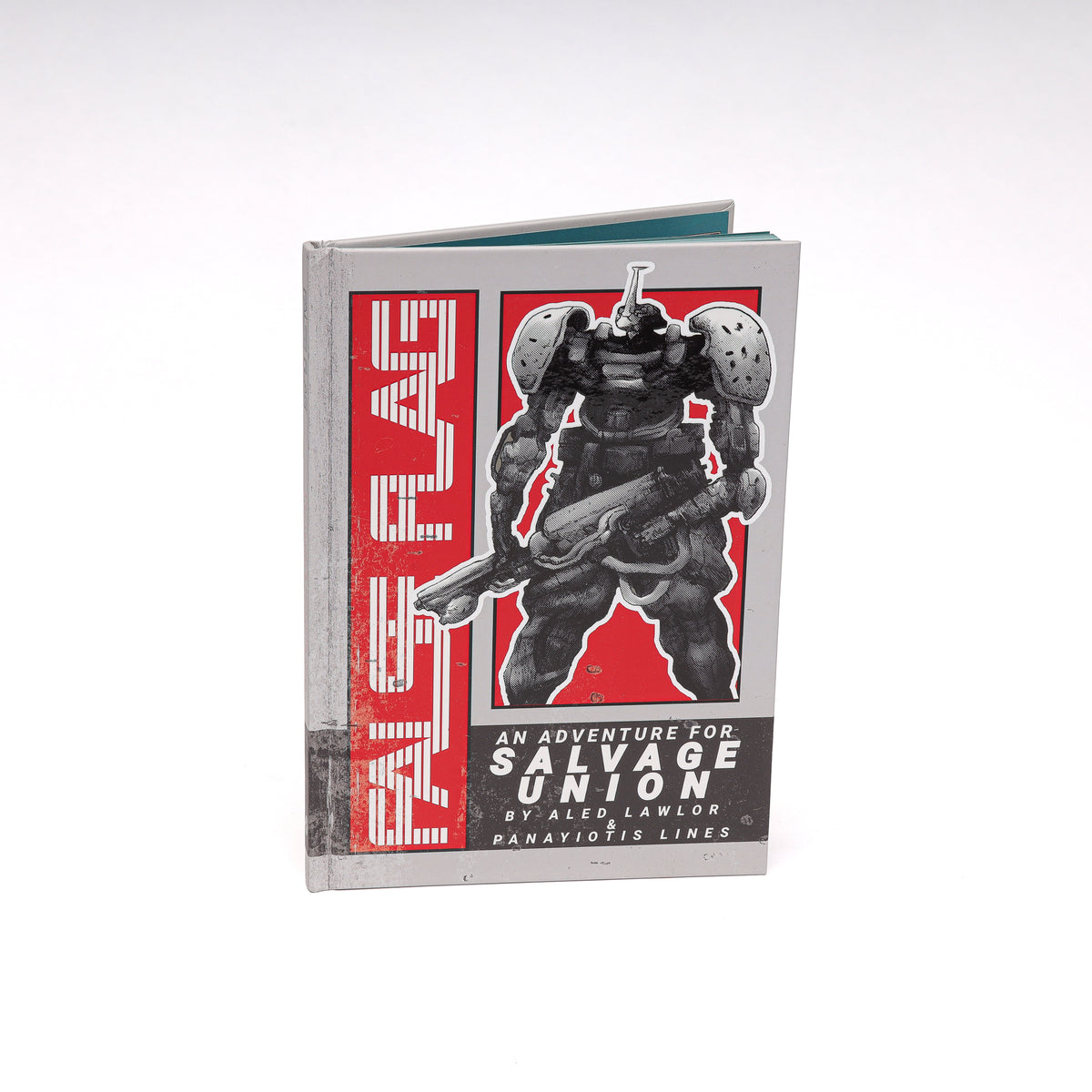

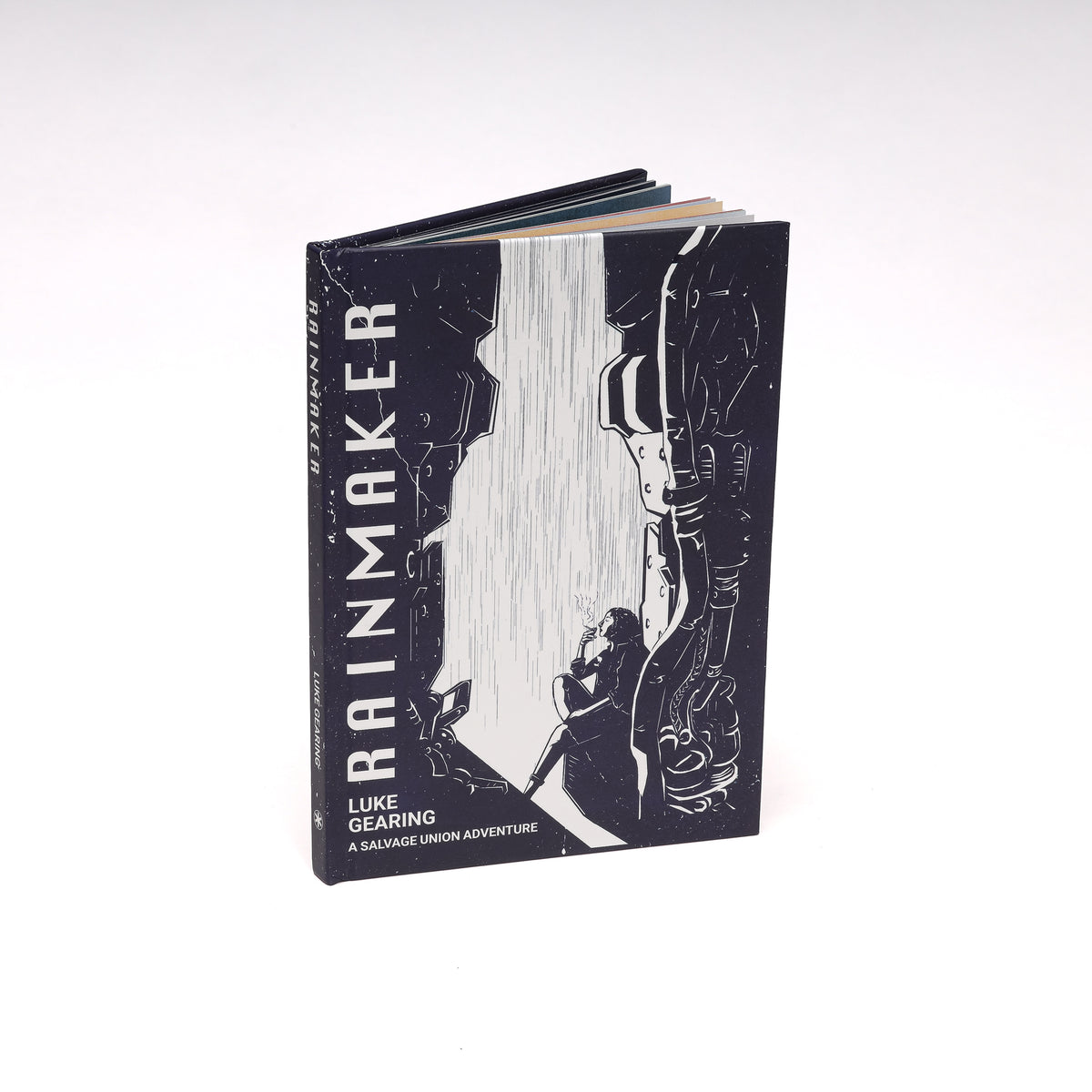

Thanks for reading! If you're interested in a trio of old school fantasy adventures check out Albion Tales.

Subscribe to the Leyline Press newsletter here to receive updates on our blogs, promotions, games and more.

Follow us on twitter @leylinepress

Follow us on facebook @leylinepress

Follow us on instagram @leylinepress

Subscribe to this blogs RSS feed by pasting this into your feed reader - https://leyline.press/blogs/leyline-press-blog.atom

This article was originally written for https://www.osrelfgame.com/

3 comments

A couple thinhgi. You have both psion and THAC0 in AD&D. Both were introduction in 2nd Edition. In AD&D you had large combat charts that were specific to each class or groups of classes. Psionics existed, but were optional rules stacking on an existing class. Also bards were optional (and rule breaking as you had to switch classes three times, from Fighter to Thief to eventually becoming a Bard).

https://leyline.press/blogs/leyline-press-blog/a-comparative-history-of-dungeons-and-dragons-becmi-1983

Howdy. The link to your comparative review of BECMI doesn’t work for me?